Private Equity: Contribution au guide multi-juridictions publié par Mondaq (en anglais).

Private Equity Q&A

1. Legal framework

1.1 Which general legislative provisions have relevance in the private equity context in your jurisdiction?

A number of legislative provisions are relevant in the private equity context in Hong Kong, as follows:

- Funds structure:

o Limited Partnership Ordinance (Cap 37); and

o Limited Partnership Fund ordinance (Cap 637).

- Funds taxation:

o Inland Revenue Ordinance (Cap 112);

o Inland Revenue (Profits Tax Exemption for Funds) (Amendment) Ordinance 2019;

o Departmental Interpretation and Practice Notes No 43 – Profits Tax – Profits Tax Exemption for Offshore Funds;

o Departmental Interpretation and Practice Notes No 51 – Profits Tax – Profits Tax Exemption for Offshore Private Equity Funds; and

o Departmental Interpretation and Practice Notes No 61 – Profits Tax – Profits Tax Exemption for Funds.

- Raising funds (limited partners):

o Securities and Future Ordinance (Cap 571) (SFO)/Securities and Futures (Professional Investor) Rules (Cap 571D);

o Organised and Serious Crime Ordinance (Cap 455); and

o Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing Ordinance (Cap 615).

- Investments:

o Company Ordinance (Cap 622);

o Competition ordinance (Cap 619); and

o Personal Data (Privacy) Ordinance (Cap 486).

1.2 What specific factors in your jurisdiction have particular relevance for and appeal to the private equity market?

Fund management companies are attracted to Hong Kong as an effective business hub close to mainland China and well positioned geographically in the Asia-Pacific region. Other factors that make it an attractive destination include:

- low profit tax (16.5%, reduced to 8.25% on the first HK$2 million profits);

- no publication of private companies’ financial statements;

- free circulation of funds (no foreign currency control);

- no restrictions on investment or repatriation of capital or remittance of profits or dividends to or from a Hong Kong company and its shareholders;

- no limits on the amount of profits that may be remitted to foreign investors, subject to restrictions in the Companies Ordinance concerning maintenance of company capital, distribution of dividends and liquidation;

- Hong Kong dollar exchange rate pegged to the US dollar;

- common law environment with few regulations, allowing for contractual freedom; and

- the presence of many providers of due diligence, financial, legal and tax support services.

2. Regulatory framework

2.1. Which regulatory authorities have relevance in the private equity context in your jurisdiction? What powers do they have?

The Companies Registry and the Inland Revenue Department (IRD) have the most relevance. Some fund management companies may also have to apply for licences from the Securities and Futures Commission (SFC).

Companies Registry: The Companies Registry provides services to allow for the incorporation of companies and the registration of all documentation required –for instance, in case of a capital increase or the issue of new shares (Form NSC1). It has powers to ensure compliance with the Companies Ordinance: for example, it may rectify typographical errors (Section 41 of the Companies Ordinance) and must rectify information on order of court (Section 42 of the Companies Ordinance). A form can be filed to report non-compliance with the Companies Ordinance. Investigation actions will be taken where appropriate.

However, the Companies Registry will not investigate a complaint where:

- the subject of the complaint concerns an internal management dispute between the directors or shareholders of the company; or

- it is claimed that members’ personal rights have been infringed.

The Companies Registry has the power to levy automatic fines for late filings of annual returns. For more serious regulatory offences under the Companies Ordinance, the penalties include fines and imprisonment, as decided upon conviction in court.

IRD: The IRD collects taxes on a territorial basis – that is, on profits sourced or derived from Hong Kong. The filing of profits tax returns follows a calendar determined by the financial year of the company. The IRD has the authority to request information from Hong Kong residents as well as from foreign tax authorities in jurisdictions with which Hong Kong has entered into a double tax treaty agreement or an exchange of tax information agreement.

Breaches of the Inland Revenue Ordinance may result in the imposition of fines and/or prison sentences, as decided upon conviction in court.

IRD Stamp Duty Bureau: The Stamp Duty Bureau is in charge of levying duty on the transfer of certain assets, including property and shares in private companies. No share transfer can be registered in the register of members of a private company without being previously stamped by the Stamp Duty Bureau. The duty is 0.2% of the highest of either the consideration paid or the pro-rated equity value of the company, based on the latest financial statements or certified management accounts of less than three months. The seller and buyer must each pay 50% of the duty.

SFC: The definition of ‘securities’ in the Securities and Futures Ordinance does not include shares or debentures of a private company. A ‘private company’ is defined as a company which is not a company limited by guarantee and whose articles:

- restrict a member’s right to transfer shares;

- limit the number of members to 50; and

- prohibit any invitation to the public to subscribe for any shares or debentures of the company.

Thus, a fund management company which carries on asset management business in relation to shares and debentures of private companies need not obtain a licence.

On the other hand, a fund management company which carries on asset management business in relation to securities in Hong Kong must obtain a licence from the SFC to conduct Type 9 regulated activity (asset management) and possibly other licences (www.sfc.hk/en/Regulatory-functions/Intermediaries/Licensing/Do-you-need-a-licence-or-registration). In addition, persons who carry out asset management activities for such fund must obtain a representative’s licence from the SFC.

2.2 What regulatory conditions typically apply to private equity transactions in your jurisdiction?

Standard representations and warranties declarations include compliance with the provisions of the Companies Ordinance and the Inland Revenue Ordinance.

Case-by-case regulatory conditions must be included as conditions precedent to private equity transactions:

- in regulated industries such as banking, insurance, securities and telecommunications. In such case any change of ownership or acquisition – even of a minority interest – must be notified or authorised in advance; or

- involving licensed activity for which a change to the licensee’s ownership must be notified (eg, money lending activity, employment agency activity or activity licensed by the SFC).

3. Structuring considerations

3.1 How are private equity transactions typically structured in your jurisdiction?

Typically, private equity management companies will incorporate a chain of holding companies for each acquisition that a particular fund makes.

A notable feature of the market in Hong Kong is that the holding companies incorporated for the buyouts are often formed offshore in jurisdictions such as the Cayman Islands or the British Virgin Islands, both for compliance with the restrictions on financial assistance and for tax reasons.

However, the unified fund exemption regime resulting from two new statutes – the Inland Revenue (Profits Tax Exemption for funds) (Amendment) Ordinance 2019 and the Limited Partnership Fund Ordinance – offers a new option to fully onshore the fund and management structure in Hong Kong, which may change the tax analysis.

Indeed, one of the key considerations for private equity funds is to ensure that, on exit, the proceeds of sale of the target can be returned to the funds with minimal delay, tax liabilities and other friction costs.

3.2 What are the potential advantages and disadvantages of the available transaction structures?

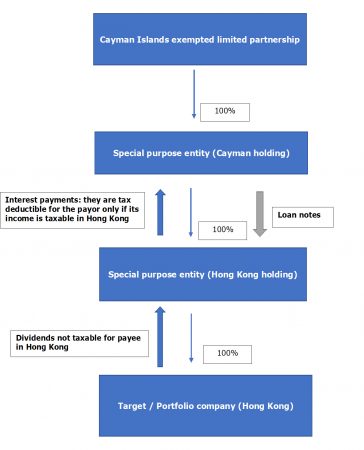

The absence of taxation for offshore income, which is usually seen as a potential advantage, may actually be a disadvantage, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The potential disadvantages of available transaction structures with offshore special purpose entities (whether domiciled in Hong Kong or not)

3.3 What funding structures are typically used for private equity transactions in your jurisdiction? What restrictions and requirements apply in this regard?

Lending: Lending from banks and financial institutions is generally available only where the target is based in Hong Kong. Cross-border private equity transactions are funded by private equity funds, which will structure their investment in equity and loan notes. Sellers that wish to maintain a minority interest may also subscribe for loan notes.

Security: Security is typically obtained through the usual mortgages and charges (fixed and floating) over the acquired assets or the shares acquired, subject to compliance with the financial assistance provisions of the Companies Ordinance (Section 275). Usually, the relative priority of security depends on the contractual arrangements negotiated between the parties.

3.4 What are the potential advantages and disadvantages of the available funding structures?

The potential advantage of the funding structure for cross-border transactions is contractual flexibility, especially as the notes holder is also a shareholder.

The potential disadvantage is the absence of leverage opportunities for cross-border private equity transactions for funds.

3.5 What specific issues should be borne in mind when structuring cross-border private equity transactions?

Attention must be paid at an early stage to both tax considerations and local regulations (for multi-jurisdictions transactions).

Tax considerations: The following checklist should be reviewed at each stage of the project (buyout, investment and exit), for each individual or entity, in each relevant jurisdiction:

- Transfer buyout funds to sellers (payment):

o Do any withholding taxes apply in the jurisdiction where the funds originate?

o Must any declaration be made to the authorities in the jurisdiction of any of the sub-targets (in case of the acquisition of a group of companies directly from the owners, rather than from a holding company)?

o Is any stamp duty due on capital increases, the issue of new shares or the transfer of shares; and if so, how is this calculated and at what rates?

- Interest paid on shareholder loans:

o Is interest fully deductible for the target or do limitations apply (eg, cap on interest rates or amount)?

- Receipt of interest on shareholder loans:

o Are interest payments subject to withholding tax and if so, at what rate? Do any tax treaty provisions apply?

- Receipt of dividends:

o Is the receipt of dividends subject to withholding tax and if so, at what rate? Do any tax treaty provisions apply?

- Receipt of capital gains in case of the sale of shares:

o Are capital gains subject to withholding tax (in the jurisdiction of the target) or capital gains tax (in the jurisdiction of the recipient – usually the fund, but sometimes the investors)?

- Receipt of liquidation bonus:

o Is a liquidation bonus subject to withholding tax (in the jurisdiction of the target) or capital gains tax (in the jurisdiction of the recipient – usually the fund, but sometimes the investors)?

Local regulations: These must also be considered at an early stage of the transaction, to ensure the smooth registration of the transfer of shares or the issue of new shares, as well as ancillary decisions (eg, changes to directors, auditors and bank signatories).

3.6 What specific issues should be borne in mind when a private equity transaction involves multiple investors?

The following broad checklist is useful:

- compliance checks, which must be commenced as early as possible to avoid a situation where the legal documentation has been agreed, but the compliance checks on some investors have not as yet been cleared;

- a check of the tax provisions applicable to each investor (see question 3.5);

- whether there is a lead investor which is formally appointed to represent some or all of the other investors for the purpose of the negotiations;

- the priorities between investors (eg, senior and mezzanine debt); and

- the procedure and arrangements for signing and completion (eg, whether e-signature is possible; power of attorney).

4. Investment process

4.1 How does the investment process typically unfold? What are the key milestones?

Key milestones include the following:

- non-disclosure agreement (NDA);

- letter of intent;

- end of due diligence and the decision to proceed with the investment (or not);

- execution of the legal documentation (signing);

- conditions precedent met or waived; and

- completion.

After the initial contact between the investor and the target, it is market practice for the investor and the target to enter into an NDA prior to exchanging non-public documents, such as financial statements and operations information. The information exchanged serves a dual purpose:

- It confirms the investor’s interest and the financial terms of the investment offer that it is prepared to make to the target; and

- It confirms the sellers’ and the target’s interest – especially if some of the sellers are prepared to reinvest all or part of the consideration to be received from the transaction.

Subject to a positive outcome of this initial stage, the lead investor shall prepare a letter of intent or an indication of interest letter, to provide a roadmap for the drafting and signing of the legal documentation. A lead investor will not spend time and effort in having a letter of intent prepared without strong interest in closing the deal. The typical binding provisions of a letter of intent include the following:

- the scope of the due diligence and the respective undertakings of the parties;

- confidentiality (repetition and reinforcement of the NDA);

- exclusivity;

- timeline; and

- costs.

Non-binding provisions regarding the terms of the legal documentation are clear guidelines for the commencement of negotiations and should be carefully reviewed by both parties prior to execution of the letter of intent.

Subject to the completion of satisfactory due diligence on the target, the drafting and negotiation of the legal documentation will typically involve the following:

- a share purchase agreement, including representations and warranties;

- an asset purchase agreement, including representations and warranties;

- a subscription agreement, including representation and warranties; or

- an investment agreement, including representations and warranties; or

- alternatively, a separate document setting out the representations and warranties;

- a shareholders’ agreement, if some payment will be made in shares and some sellers will become shareholders in the acquisition special purpose entity (ie, the target is not wholly acquired); and

- a management package, including new employment or service agreements for managers and a long-term incentive plan.

4.2 What level of due diligence does the private equity firm typically conduct into the target?

Prior vendor due diligence is highly recommended, in order to prepare for the intense scrutiny to which the private equity firm will subject the target – in particular, in relation to its business plan, forecasts and quality of earnings. An evaluation of the management team is also an early part of the due diligence.

Subject to satisfactory financial due diligence as indicated above, the private equity firm will instruct service providers for legal and tax due diligence to review the following, among others:

- compliance (eg, Companies Registry and Inland Revenue Department staff-related filings, private data and other relevant specific rules, such as the Money Lenders Ordinance and the Securities and Futures Ordinance);

- employment contracts and related documents;

- commercial documents (standards and samples); and

- corporate documents (including any shareholders’ agreement).

It is also important to check that the target has appropriate processes in place beforehand, as non-existent or insufficient processes will ultimately hinder the target’s growth capacity post-investment.

4.3 What disclosure requirements and restrictions may apply throughout the investment process, for both the private equity firm and the target?

- Private equity firm: Confidentiality undertakings to use confidential information for the purpose of investment in the target only.

- Target: Confidentiality and exclusivity agreements prior to the due diligence, acknowledging the investment made by the private equity firm.

4.4 What advisers and other stakeholders are involved in the investment process?

For larger investments, M&A advisory consultants often assist the target management team. For due diligence, they are split between audit firms with an M&A department and legal firms. The law firm hired for the due diligence may be different from that advising on the legal documentation.

The stakeholders from the target are the chief financial officer, the management team and more specifically the chief executive officer and his or her team.

5. Investment terms

5.1 What closing mechanisms are typically used for private equity transactions in your jurisdiction (eg, locked box; closing accounts) and what factors influence the choice of mechanism?

The locked box mechanism is not very popular in Hong Kong, as parties often do not feel confident that the agreed amount will ultimately be fair. According to a recent report [MoFo 202 Asia Buyouts Report: Update on Deal Terms – Part 1: Pricing the Deal], locked box mechanisms are seen only in exit deals (ie, where the private equity firm is the seller).

The parties usually rely on completion account mechanisms.

5.2 Are break fees permitted in your jurisdiction? If so, under what conditions will they generally be payable? What restrictions or other considerations should be addressed in formulating break fees?

Break fees are permitted in Hong Kong, subject to the common law general restrictions on penalty clauses. The amount of break fees should reflect the actual costs incurred by the private equity firm in terms of advisers’ fees and the time of its team.

Break fees are generally agreed in the letter of intent, in case of breach of exclusivity by the target.

5.3 How is risk typically allocated between the parties?

Extensive representations and warranties are requested from the sellers, with no threshold and a cap equal to the price or no cap for core representations and warranties such as ownership and title, power and authority.

The identified risks are dealt with differently – either reflected in the price or, in case of uncertainty, agreed in an advance indemnity in case of occurrence.

The sellers’ undertakings to indemnify the private equity firm are typically several (ie, each seller is liable only in proportion to its shareholding), unless the relationship between the sellers justifies joint and several liability (ie, each seller is liable for the whole amount of the claim).

Mechanisms to guarantee the payment of the claims include:

- securities over liquid assets held by a bank;

- escrow of part of the purchase price (with the amount held in escrow decreasing with the passing of time); and

- earn-out provisions (where the seller remains a key manager).

5.4 What representations and warranties will typically be made and what are the consequences of breach? Is warranty and indemnity insurance commonly used?

The extent of the representations and warranties is typically broad. In case of breach, payment is subject to compliance with the steps set out in the agreement (eg, notification of possible claims; participation of the sellers to the claim in varying degrees), until an agreement on the damage or a final court decision is secured.

Warranty and indemnity insurance is not yet common practice in Hong Kong.

6. Management considerations

6.1 How are management incentive schemes typically structured in your jurisdiction? What are the potential advantages and disadvantages of these different structures?

Incentive plans for management are generally structured on a three to five-year period.

However, short-term incentives based on annual results are not uncommon. If the fund decides to take the company public, stock options (with or without lock-ups) are a typical incentive.

Another common incentive to ensure that the management team is committed to the business of the target is the ratchet mechanism. For instance, management performance may trigger:

- redeemable shares issued to the private equity firm to be redeemed, with a relution effect on the management share capital; or,

- the alteration of rights attached to classes of shares.

The key advantage of management incentive schemes is the alignment of the interests of the private equity firm with those of the management team. In our view, the disadvantage is the complexity of some mechanisms, whose implementation costs in terms of resources may be too high for some targets.

6.2 What are the tax implications of these different structures? What strategies are available to mitigate tax exposure?

The tax implications must be reviewed from the perspective of both the employer (special vehicle entity or target) and the beneficiaries (employees or officers of the target).

For long-term incentive plans that allow beneficiaries to apply for new shares, the capital gain realised upon vesting of shares is subject to salaries tax; thus, it is usually better for employees to have the option to purchase shares at market price. This in turns raises the issue of funding for employees.

The ratchet mechanisms referred to above are neutral from a tax perspective.

6.3 What rights are typically granted and what restrictions typically apply to manager shareholders?

Manager shareholders will typically be offered a new remuneration package, including:

- a revised job description in line with the expectations of the private equity firm;

- tighter restrictive covenants comprising non-compete and confidentiality clauses, as well as provisions on ‘gardening leave’ to mitigate risks where key team members resign or in case of dismissal;

- a long-term incentive plan with three to five-year targets; and

- a short-term incentive with bonus tied to annual performance.

6.4 What leaver provisions typically apply to manager shareholders and how are ‘good’ and ‘bad’ leavers typically defined?

Leaver provisions typically provide for a call option in favour of the target with a substitution clause, with the price for the option depending on different factors – for example:

- whether there was an initial lock-down period; and

- whether the manager shareholder is considered a good leaver or bad leaver.

The discount is usually between 10% and 50% of the market price.

Typical good leaver events include serious incapacity or death or after a lock-up period of three to five years. Some clauses will include serious illness in a close family member (spouse or child).

Typical bad-lever events include resignation (except for a cause above or after the lock-up period) or termination (with or without cause).

7. Governance and oversight

7.1 What are the typical governance arrangements of private equity portfolio companies?

Typical governance arrangements include the following:

- enhanced information rights (eg, quarterly reporting, access to the company’s documents, advance discussion of budget or periodical reassessment of the business plan);

- the appointment of at least one representative to the board of directors;

- reserved matters of the board which require either or both of the participation and the vote of the private equity firm; and

- reserved matters of the members which require either or both of the participation and vote of the private equity firm.

7.2 What considerations should a private equity firm take into account when putting forward nominees to the board of the portfolio company?

Private equity firms tend to appoint their own team members in order to have full control over decisions.

Based on our experience, private equity firms should look for a balanced board with representatives of the founders/management as well as investors and independent non-executive directors (INEDs). The appointment of INEDs will support quality discussions and minimise the risk of polarisation in situations where the interests of the management team and those of the investors are not aligned.

7.3 Can the private equity firm and/or its nominated directors typically veto significant corporate decisions of the portfolio company?

Most private equity firms will insist on having veto rights on significant corporate decisions of the portfolio company. It is thus very important to have an adequate definition of these types of decisions: the veto should concern only those decisions which are material with regard to their subject or the amount at stake, in order to avoid paralysing the management of the company. The criteria should be revised from time to time, to ensure that they remain relevant to the size of the business.

7.4 What other tools and strategies are available to the private equity firm to monitor and influence the performance of the portfolio company?

The most dynamic private equity firms leverage their networks to create opportunities for their portfolio companies, and provide ‘on-demand’ coaching in critical and fast-evolving areas such as finance and logistics. Other advantages afforded by private equity firms in monitoring and influencing the performance of the portfolio company include:

- access to new markets;

- expertise in supporting buy-and-build strategies;

- the ability to provide follow-on funding; and

- the strength of board appointments.

8. Exit

8.1 What exit strategies are typically negotiated by private equity firms in your jurisdiction?

Private buyout and initial public offerings (IPOs) are the typical exit options.

A private buyout is most likely to be effected by another private equity fund or a buyer in the same industry (eg, a competitor, supplier or client).

In case of insolvency of the target, a private buyout of the target or some of its assets may be an option. In case of winding-up (voluntary or involuntary liquidation), a liquidator will be appointed by the Official Receiver’s Office, tasked with the sale of assets and the payment of creditors. Any cash remaining will be returned to the shareholders in proportion to their shareholdings or possibly by application of liquidation preference rights.

8.2 What specific legal and regulatory considerations (if any) must be borne in mind when pursuing each of these different strategies in your jurisdiction?

IPOs require careful anticipation and preparation to ensure that the portfolio company meets the listing requirements (Main Board or Growth Enterprise Market), and is prepared for ongoing compliance with the listing rules.

9. Tax considerations

9.1 What are the key tax considerations for private equity transactions in your jurisdiction?

Stamp duty

In the case of a share acquisition of a Hong Kong company, each of the buyer and the seller must execute a contract note. Each contract note is liable to stamp duty at the rate of 0.1% of the higher of the consideration for the shares or the pro-rated equity value of the shares transferred (the total stamp duty exposure is 0.2%).

An exemption applies for shares transferred between companies with a common shareholding of 90% or more (among other conditions). An application must be made to the Collector of Stamp Revenue to take advantage of this exemption.

Stamp duty must be paid before the transfer of shares can be registered in the books of the target and within the timeframes specified in the Stamp Duty Ordinance.

Deductibility of interest and financing costs: The availability of tax deductions for interest expenses must be considered. Interest is deductible in Hong Kong only if:

- it is incurred to derive assessable income; and

- it is paid to either a bank or a lender liable to tax on the interest income.

If a Hong Kong holding company is used to acquire a Hong Kong target and debt (whether shareholder or third party) is injected at the holding company level to finance the buyout, to the extent that the investment in the target generates no assessable profits for the Hong Kong holding company, the interest expense will be non-deductible (see question 3.2). Therefore, since dividends from the Hong Kong target are exempt from tax, the deductibility of the financing costs will be an issue in this case.

There are no thin capitalisation rules for Hong Kong companies.

Accumulated losses: Generally, companies can carry forward losses for set-off in subsequent tax years. However, anti-avoidance provisions in the Inland Revenue Ordinance allow the Commissioner of Inland Revenue to refuse to offset losses brought forward if he or she is satisfied that the sole or dominant purpose of a change in shareholding is the utilisation of those losses to obtain a tax benefit. Further due diligence is required if a target has accumulated losses and a premium is sought for the benefit of the tax losses.

The fund may also seek an advance ruling from the Inland Revenue Department to confirm that the losses will remain available for set-off by the target after the buyout.

Withholding tax: Payments of interest or dividends by a Hong Kong target to non-residents is not subject to withholding tax, as Hong Kong does not impose withholding tax on interest and dividends.

However, if the Hong Kong portfolio company makes royalty payments to a non-resident fund for the use of intellectual property in Hong Kong (or for use outside Hong Kong if the payment is deductible against profits assessable in Hong Kong), the Hong Kong portfolio company will be required to withhold tax. The amount of the withholding tax is calculated as either 30% or 100% of the amount of profits tax payable on the payment (effectively 4.95% or 16.5% of the payment, based on the current profits tax rate of 16.5%). The higher rate applies if the intellectual property was previously owned in Hong Kong.

Exit considerations: A key issue is whether the investment in the target is regarded for tax purposes as being held as a trading asset or for long-term investment. As Hong Kong does not tax capital gains, this issue is particularly important.

If the investment in the target is regarded for tax purposes as being held for long-term investment, the profits from the sale of the investment will not be subject to Hong Kong tax.

On the other hand, if the investment in the target is regarded for tax purposes as being held as a revenue asset, the profits from the sale of the investment will be assessable profits. The issue of whether a profit is capital or revenue in nature is essentially a question of fact and depends on many factors, including the intention of the taxpayer at the time of acquisition; and good documentation for the purpose of the buyout is essential to protect the tax position.

9.2 What indirect tax risks and opportunities can arise from private equity transactions in your jurisdiction?

In terms of risk, the board members of Hong Kong portfolio companies can be held liable for:

- non-compliance with the Companies Ordinance provisions on book keeping and the preparation; or

- non-payment of salaries as provided for in the Employment Ordinance.

In most cases, it is a valid defence to have delegated this role to someone capable. Furthermore, directors’ and officers’ insurance is largely available in Hong Kong and will provide protection, except in case of fraud.

In terms of opportunities, the principle that capital gains realised by individual investors are normally tax exempt presents opportunities for the individual shareholders of Hong Kong portfolio companies (if they reside in Hong Kong), and also for individual Hong Kong-based co-investors of private equity firms.

9.3 What preferred tax strategies are typically adopted in private equity transactions in your jurisdiction?

The structure commonly used by private equity funds to manage the funds raised from their investor base is the limited partnership, which is commonly constituted in the Cayman Islands for tax purposes. The investors hold limited partnership interests in the partnership, and a general partner has day-to-day management control of the partnership and its operations. The general partner typically delegates the investment management functions to an investment manager or investment adviser in Hong Kong.

The effect of the new unified exemption regime introduced by new provisions of Hong Kong law – the Limited Partnership Fund Ordinance and the Inland Revenue (Profits Tax Exemption for Funds) (Amendment) Ordinance (see question 3.1) – remains to be seen.

10. Trends and predictions

10.1 How would you describe the current private equity landscape and prevailing trends in your jurisdiction? What are regarded as the key opportunities and main challenges for the coming 12 months?

The new unified exemption regime set out in the Limited Partnership Fund Ordinance and the Inland Revenue (Profits Tax Exemption for Funds) (Amendment) Ordinance (see question 3.1 above) may change the private equity landscape by bringing to Hong Kong funds which were previously registered offshore in the Cayman Islands. Subject to similar taxation, it is likely that this new structuring option will prove popular.

10.2 Are any developments anticipated in the next 12 months, including any proposed legislative reforms in the legal or tax framework?

See question 10.1.

11. Tips and traps

11.1 What are your tips to maximise the opportunities that private equity presents in your jurisdiction, for both investors and targets, and what potential issues or limitations would you highlight?

The Limited Partnership Fund Ordinance offers the opportunity to set up funds in Hong Kong with the contractual flexibility usually associated with Cayman Islands exempted limited partnerships, which are now subject to more vigorous regulatory oversight and reporting as a result of the efforts of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development to address base erosion and profit shifting.

Both investors and targets can benefit from Hong Kong’s business and financial infrastructure (see www.doingbusiness.org/en/rankings), and its status as a financial centre (the Hong Kong Stock Exchange was ranked first in 2019 by amount of funds raised for initial public offerings – www.hkex.com.hk/-/media/HKEX-Market/Market-Data/Statistics/Consolidated-Reports/Annual-Market-Statistics/2019-Market-Statistics.pdf).

Potential issues stem from the new National Security Law, passed on 30 June 2020 – especially in relation to data-driven businesses and tax treatment for carried interest (an area of taxation which the unified exemption regime has not clarified).